def render_c(filename):

from IPython.display import Markdown

with open(filename) as f:

contents = f.read()

return Markdown("```c\n" + contents + "```\n")

Using #pragma omp task

Up to now, we’ve been expressing parallelism for iterating over an array.

render_c('task_dep.4.c')

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int x = 1;

#pragma omp parallel

#pragma omp single

{

#pragma omp task shared(x) depend(out: x)

x = 2;

#pragma omp task shared(x) depend(in: x)

printf("x + 1 = %d. ", x+1);

#pragma omp task shared(x) depend(in: x)

printf("x + 2 = %d. ", x+2);

}

puts("");

return 0;

}

!make CFLAGS=-fopenmp -B task_dep.4

cc -fopenmp task_dep.4.c -o task_dep.4

!for i in {1..10}; do ./task_dep.4; done

x + 2 = 4. x + 1 = 3.

x + 1 = 3. x + 2 = 4.

x + 2 = 4. x + 1 = 3.

x + 1 = 3. x + 2 = 4.

x + 2 = 4. x + 1 = 3.

x + 1 = 3. x + 2 = 4.

x + 1 = 3. x + 2 = 4.

x + 2 = 4. x + 1 = 3.

x + 2 = 4. x + 1 = 3.

x + 2 = 4. x + 1 = 3.

render_c('task_dep.4inout.c')

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int x = 1;

#pragma omp parallel

#pragma omp single

{

#pragma omp task shared(x) depend(out: x)

x = 2;

#pragma omp task shared(x) depend(inout: x)

printf("x + 1 = %d. ", x+1);

#pragma omp task shared(x) depend(in: x)

printf("x + 2 = %d. ", x+2);

}

puts("");

return 0;

}

!make CFLAGS=-fopenmp -B task_dep.4inout

cc -fopenmp task_dep.4inout.c -o task_dep.4inout

!for i in {1..10}; do ./task_dep.4inout; done

x + 1 = 3. x + 2 = 4.

x + 1 = 3. x + 2 = 4.

x + 1 = 3. x + 2 = 4.

x + 1 = 3. x + 2 = 4.

x + 1 = 3. x + 2 = 4.

x + 1 = 3. x + 2 = 4.

x + 1 = 3. x + 2 = 4.

x + 1 = 3. x + 2 = 4.

x + 1 = 3. x + 2 = 4.

x + 1 = 3. x + 2 = 4.

Computing the Fibonacci numbers with OpenMP

Fibonacci numbers are defined by the recurrence

\begin{align}

F_0 &= 0

F_1 &= 1

Fn &= F{n-1} + F_{n-2}

\end{align}

render_c('fib.c')

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

long fib(long n) {

if (n < 2) return n;

return fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

if (argc != 2) {

fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s N\n", argv[0]);

return 1;

}

long N = atol(argv[1]);

long fibs[N];

#pragma omp parallel for

for (long i=0; i<N; i++)

fibs[i] = fib(i+1);

for (long i=0; i<N; i++)

printf("%2ld: %5ld\n", i+1, fibs[i]);

return 0;

}

!make CFLAGS='-O2 -march=native -fopenmp -Wall' -B fib

cc -O2 -march=native -fopenmp -Wall fib.c -o fib

!OMP_NUM_THREADS=4 time ./fib 40

1: 1

2: 1

3: 2

4: 3

5: 5

6: 8

7: 13

8: 21

9: 34

10: 55

11: 89

12: 144

13: 233

14: 377

15: 610

16: 987

17: 1597

18: 2584

19: 4181

20: 6765

21: 10946

22: 17711

23: 28657

24: 46368

25: 75025

26: 121393

27: 196418

28: 317811

29: 514229

30: 832040

31: 1346269

32: 2178309

33: 3524578

34: 5702887

35: 9227465

36: 14930352

37: 24157817

38: 39088169

39: 63245986

40: 102334155

0.85user 0.00system 0:00.78elapsed 109%CPU (0avgtext+0avgdata 2044maxresident)k

0inputs+0outputs (0major+99minor)pagefaults 0swaps

Use tasks

render_c('fib2.c')

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

long fib(long n) {

if (n < 2) return n;

long n1, n2;

#pragma omp task shared(n1)

n1 = fib(n - 1);

#pragma omp task shared(n2)

n2 = fib(n - 2);

#pragma omp taskwait

return n1 + n2;

}

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

if (argc != 2) {

fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s N\n", argv[0]);

return 1;

}

long N = atol(argv[1]);

long fibs[N];

#pragma omp parallel

#pragma omp single nowait

{

for (long i=0; i<N; i++)

fibs[i] = fib(i+1);

}

for (long i=0; i<N; i++)

printf("%2ld: %5ld\n", i+1, fibs[i]);

return 0;

}

!make CFLAGS='-O2 -march=native -fopenmp -Wall' fib2

make: 'fib2' is up to date.

!OMP_NUM_THREADS=2 time ./fib2 30

1: 1

2: 1

3: 2

4: 3

5: 5

6: 8

7: 13

8: 21

9: 34

10: 55

11: 89

12: 144

13: 233

14: 377

15: 610

16: 987

17: 1597

18: 2584

19: 4181

20: 6765

21: 10946

22: 17711

23: 28657

24: 46368

25: 75025

26: 121393

27: 196418

28: 317811

29: 514229

30: 832040

2.42user 0.81system 0:02.54elapsed 127%CPU (0avgtext+0avgdata 2028maxresident)k

0inputs+0outputs (0major+100minor)pagefaults 0swaps

It’s expensive to create tasks when

nis small, even with only one thread. How can we cut down on that overhead?render_c('fib3.c')#include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> long fib(long n) { if (n < 2) return n; if (n < 30) return fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2); long n1, n2; #pragma omp task shared(n1) n1 = fib(n - 1); #pragma omp task shared(n2) n2 = fib(n - 2); #pragma omp taskwait return n1 + n2; } int main(int argc, char **argv) { if (argc != 2) { fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s N\n", argv[0]); return 1; } long N = atol(argv[1]); long fibs[N]; #pragma omp parallel #pragma omp single nowait { for (long i=0; i<N; i++) fibs[i] = fib(i+1); } for (long i=0; i<N; i++) printf("%2ld: %5ld\n", i+1, fibs[i]); return 0; }!make CFLAGS='-O2 -march=native -fopenmp -Wall' fib3cc -O2 -march=native -fopenmp -Wall fib3.c -o fib3

!OMP_NUM_THREADS=3 time ./fib3 401: 1 2: 1 3: 2 4: 3 5: 5 6: 8 7: 13 8: 21 9: 34 10: 55 11: 89 12: 144 13: 233 14: 377 15: 610 16: 987 17: 1597 18: 2584 19: 4181 20: 6765 21: 10946 22: 17711 23: 28657 24: 46368 25: 75025 26: 121393 27: 196418 28: 317811 29: 514229 30: 832040 31: 1346269 32: 2178309 33: 3524578 34: 5702887 35: 9227465 36: 14930352 37: 24157817 38: 39088169 39: 63245986 40: 102334155 3.56user 0.00system 0:01.27elapsed 280%CPU (0avgtext+0avgdata 1920maxresident)k 0inputs+0outputs (0major+103minor)pagefaults 0swaps

This is just slower, even with one thread. Why might that be?

render_c('fib4.c')#include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> long fib_seq(long n) { if (n < 2) return n; return fib_seq(n - 1) + fib_seq(n - 2); } long fib(long n) { if (n < 30) return fib_seq(n); long n1, n2; #pragma omp task shared(n1) n1 = fib(n - 1); #pragma omp task shared(n2) n2 = fib(n - 2); #pragma omp taskwait return n1 + n2; } int main(int argc, char **argv) { if (argc != 2) { fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s N\n", argv[0]); return 1; } long N = atol(argv[1]); long fibs[N]; #pragma omp parallel #pragma omp single nowait { for (long i=0; i<N; i++) fibs[i] = fib(i+1); } for (long i=0; i<N; i++) printf("%2ld: %5ld\n", i+1, fibs[i]); return 0; }!make CFLAGS='-O2 -march=native -fopenmp -Wall' fib4make: ‘fib4’ is up to date.

!OMP_NUM_THREADS=2 time ./fib4 401: 1 2: 1 3: 2 4: 3 5: 5 6: 8 7: 13 8: 21 9: 34 10: 55 11: 89 12: 144 13: 233 14: 377 15: 610 16: 987 17: 1597 18: 2584 19: 4181 20: 6765 21: 10946 22: 17711 23: 28657 24: 46368 25: 75025 26: 121393 27: 196418 28: 317811 29: 514229 30: 832040 31: 1346269 32: 2178309 33: 3524578 34: 5702887 35: 9227465 36: 14930352 37: 24157817 38: 39088169 39: 63245986 40: 102334155 0.94user 0.00system 0:00.53elapsed 177%CPU (0avgtext+0avgdata 2040maxresident)k 8inputs+0outputs (0major+97minor)pagefaults 0swaps

Alt: schedule(static,1)

render_c('fib5.c')

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

long fib(long n) {

if (n < 2) return n;

return fib(n - 1) + fib(n - 2);

}

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

if (argc != 2) {

fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s N\n", argv[0]);

return 1;

}

long N = atol(argv[1]);

long fibs[N];

#pragma omp parallel for schedule(static,1)

for (long i=0; i<N; i++)

fibs[i] = fib(i+1);

for (long i=0; i<N; i++)

printf("%2ld: %5ld\n", i+1, fibs[i]);

return 0;

}

!make CFLAGS='-O2 -march=native -fopenmp -Wall' fib5

make: 'fib5' is up to date.

!OMP_NUM_THREADS=2 time ./fib5 40

1: 1

2: 1

3: 2

4: 3

5: 5

6: 8

7: 13

8: 21

9: 34

10: 55

11: 89

12: 144

13: 233

14: 377

15: 610

16: 987

17: 1597

18: 2584

19: 4181

20: 6765

21: 10946

22: 17711

23: 28657

24: 46368

25: 75025

26: 121393

27: 196418

28: 317811

29: 514229

30: 832040

31: 1346269

32: 2178309

33: 3524578

34: 5702887

35: 9227465

36: 14930352

37: 24157817

38: 39088169

39: 63245986

40: 102334155

0.88user 0.00system 0:00.54elapsed 161%CPU (0avgtext+0avgdata 1908maxresident)k

8inputs+0outputs (0major+93minor)pagefaults 0swaps

Better math

render_c('fib6.c')

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

if (argc != 2) {

fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s N\n", argv[0]);

return 1;

}

long N = atol(argv[1]);

long fibs[N];

fibs[0] = 1;

fibs[1] = 2;

for (long i=2; i<N; i++)

fibs[i] = fibs[i-1] + fibs[i-2];

for (long i=0; i<N; i++)

printf("%2ld: %5ld\n", i+1, fibs[i]);

return 0;

}

!make CFLAGS='-O2 -march=native -fopenmp -Wall' fib6

cc -O2 -march=native -fopenmp -Wall fib6.c -o fib6

!time ./fib6 100

1: 1

2: 2

3: 3

4: 5

5: 8

6: 13

7: 21

8: 34

9: 55

10: 89

11: 144

12: 233

13: 377

14: 610

15: 987

16: 1597

17: 2584

18: 4181

19: 6765

20: 10946

21: 17711

22: 28657

23: 46368

24: 75025

25: 121393

26: 196418

27: 317811

28: 514229

29: 832040

30: 1346269

31: 2178309

32: 3524578

33: 5702887

34: 9227465

35: 14930352

36: 24157817

37: 39088169

38: 63245986

39: 102334155

40: 165580141

41: 267914296

42: 433494437

43: 701408733

44: 1134903170

45: 1836311903

46: 2971215073

47: 4807526976

48: 7778742049

49: 12586269025

50: 20365011074

51: 32951280099

52: 53316291173

53: 86267571272

54: 139583862445

55: 225851433717

56: 365435296162

57: 591286729879

58: 956722026041

59: 1548008755920

60: 2504730781961

61: 4052739537881

62: 6557470319842

63: 10610209857723

64: 17167680177565

65: 27777890035288

66: 44945570212853

67: 72723460248141

68: 117669030460994

69: 190392490709135

70: 308061521170129

71: 498454011879264

72: 806515533049393

73: 1304969544928657

74: 2111485077978050

75: 3416454622906707

76: 5527939700884757

77: 8944394323791464

78: 14472334024676221

79: 23416728348467685

80: 37889062373143906

81: 61305790721611591

82: 99194853094755497

83: 160500643816367088

84: 259695496911122585

85: 420196140727489673

86: 679891637638612258

87: 1100087778366101931

88: 1779979416004714189

89: 2880067194370816120

90: 4660046610375530309

91: 7540113804746346429

92: -6246583658587674878

93: 1293530146158671551

94: -4953053512429003327

95: -3659523366270331776

96: -8612576878699335103

97: 6174643828739884737

98: -2437933049959450366

99: 3736710778780434371

100: 1298777728820984005

0.002 real 0.002 user 0.000 sys 99.42 cpu

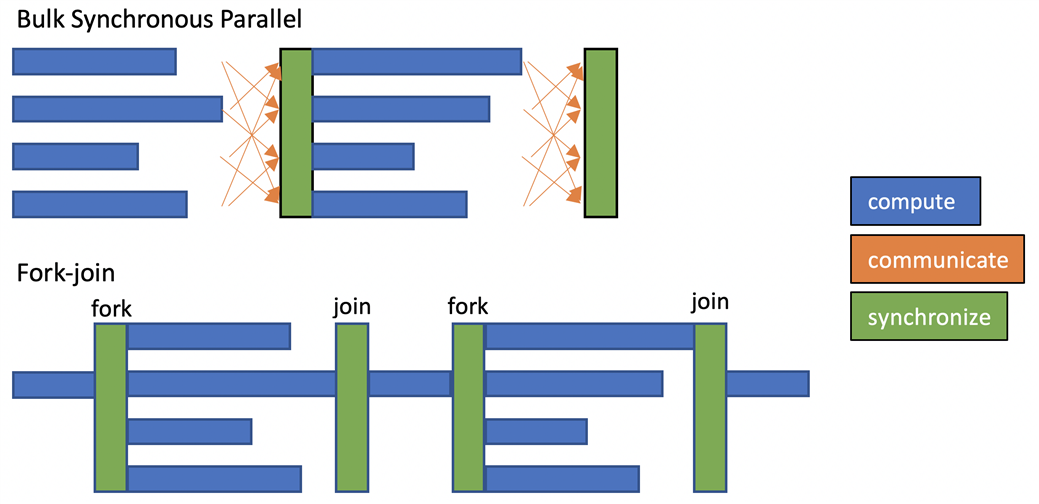

To fork/join or to task?

When the work unit size and compute speed is predictable, we can partition work in advance and schedule with omp for to achieve load balance.

Satisfying both criteria is often hard:

- Adaptive algorithms, adaptive physics, implicit constitutive models

- AVX throttling, thermal throttling, network or file system contention, OS jitter

Fork/join and barriers are also high overhead, so we might want to express data dependencies more precisely.

For tasking to be efficient, it relies on overdecomposition, creating more work units than there are processing units. For many numerical algorithms, there is some overhead to overdecomposition. For example, in array processing, a halo/fringe/ghost/overlap region might need to be computed as part of each work patch, leading to time models along the lines of $$ t{\text{tile}}(n) = t{\text{latency}} + \frac{(n+2)^3}{R} $$ where $R$ is the processing rate. In addition to the latency, the overhead fraction is $$ \frac{(n+2)^3 - n^3}{n^3} \approx 6/n $$ indicating that larger $n$ should be more efficient.

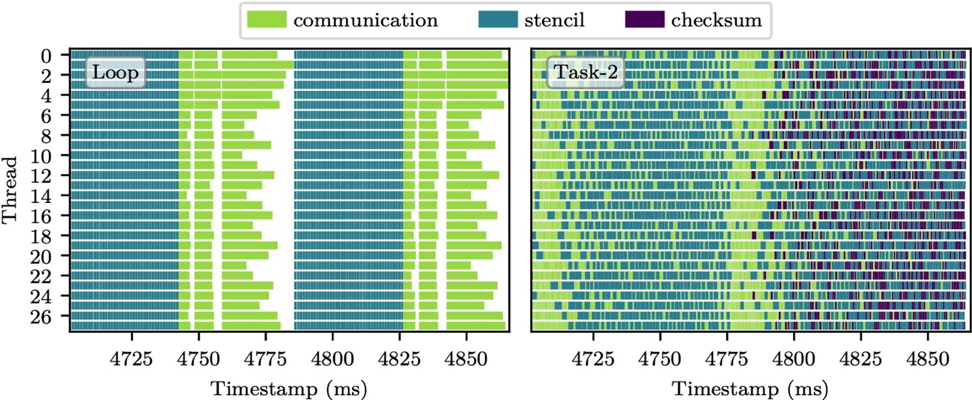

However, if this overhead is acceptable and you still have load balancing challenges, tasking can be a solution. (Example from a recent blog/talk.)

Computational depth and the critical path

Consider the block Cholesky factorization algorithm (applying to the lower-triangular matrix $A$).

Expressing essential data dependencies, this results in the following directed acyclic graph (DAG). No parallel algorithm can complete in less time than it takes for a sequential algorithm to perform each operation along the critical path (i.e., the minimum depth of this graph such that all arrows point downward).

Figures from Agullo et al (2016): Are Static Schedules so Bad? A Case Study on Cholesky Factorization, which is an interesting counterpoint to the common narrative pushing dynamic scheduling.

Question: what is the computational depth of summing an array?

$$ \sum_{i=0}^{N-1} a_i $$

double sum = 0;

for (int i=0; i<N; i++)

sum += array[i];

Given an arbitrarily large number $P$ of processing units, what is the smallest computational depth to compute this mathematical result? (You’re free to use any associativity.)